Blexbolex «Ballad»

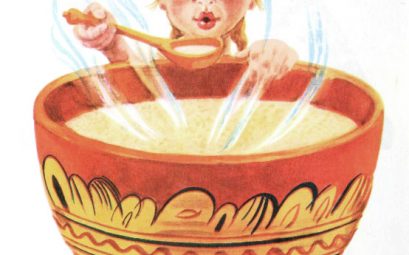

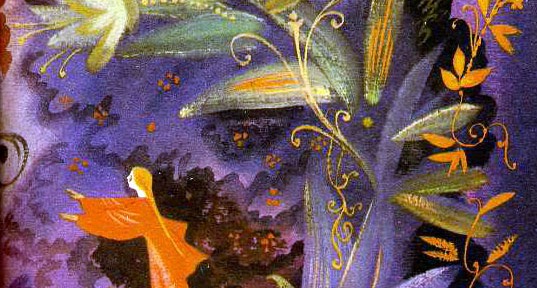

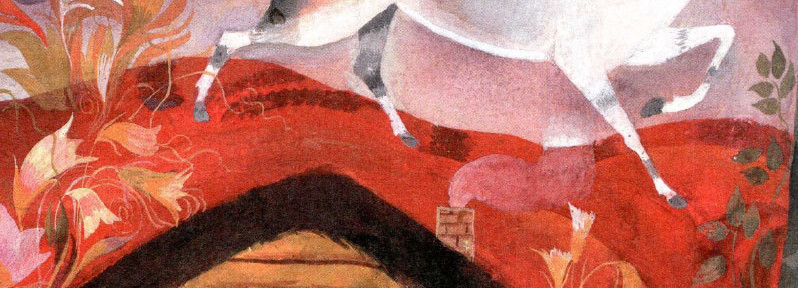

«Ballad» is a story, and like all great stories it deepens with each retelling. «Ballad» builds over seven sequences. The first has three images: school, path, home. The next builds upon the first, giving us: school, street, path, forest, home. The next five sequences take up this story, but with new words and images that nearly double the previous sequence. Here a child encounters the world as he returns home from school, and we see his small world become enormous. This story is as old as the world. It happens every day.

Blexbolex is a bold, highly talented graphic artist. In addition to creating comics, he’s been internationally acclaimed for Seasons, selected as a 2012 New York Times Book Review Best Illustrated Book of the Year; and People.